Author: Pieter de Klerk

A leading South African Financial Services Group collaborated with JVR Consulting Psychologists (JVR) to assist with developing a Female Leadership Development Programme. This initiative required JVR’s specialised skills in assessing the leadership behaviours of 19 existing female managers, pinpointing opportunities to enhance their leadership potential for them to be considered for senior female leadership roles within the organisation, but also to drive specific leadership development initiatives. By leveraging a multi-method, science-based approach, the assessment process delivered actionable insights to drive individual and group development, but also contributed to a strategic organisational imperative, which is Female Leadership Development Programmes.

The Goal: Unlocking Leadership Potential in Women

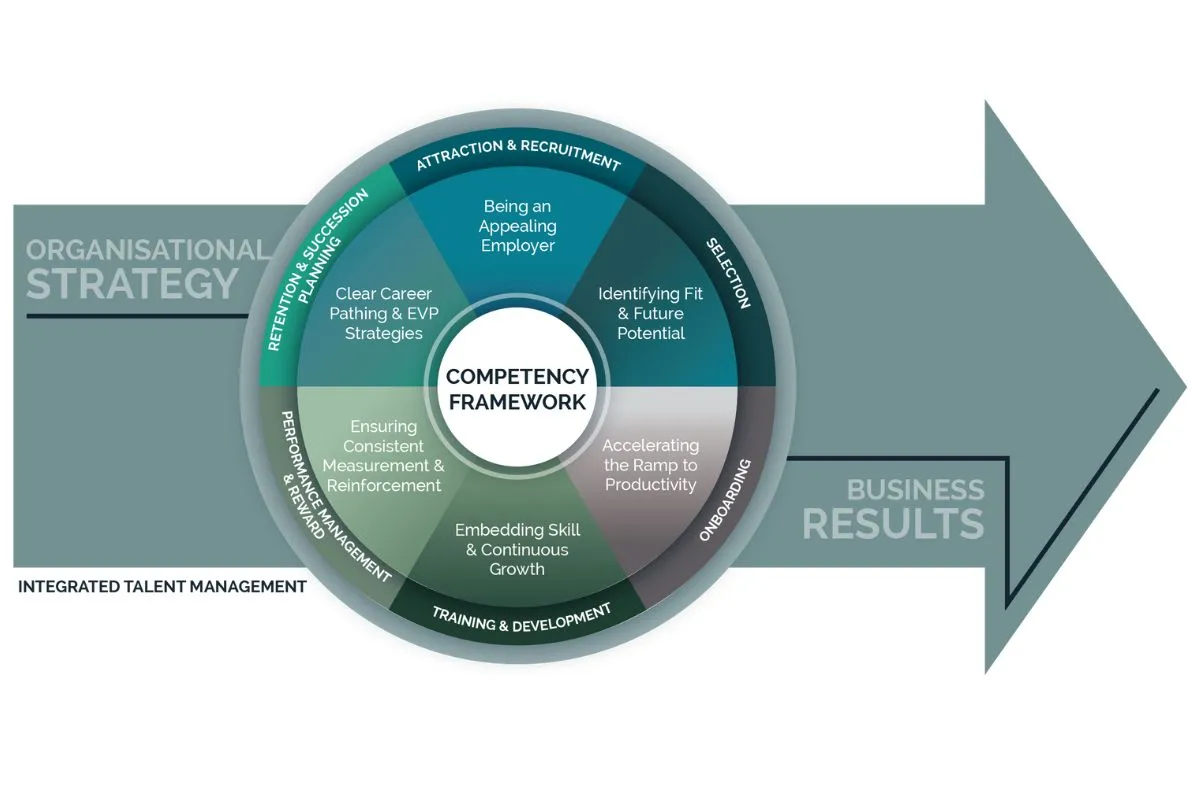

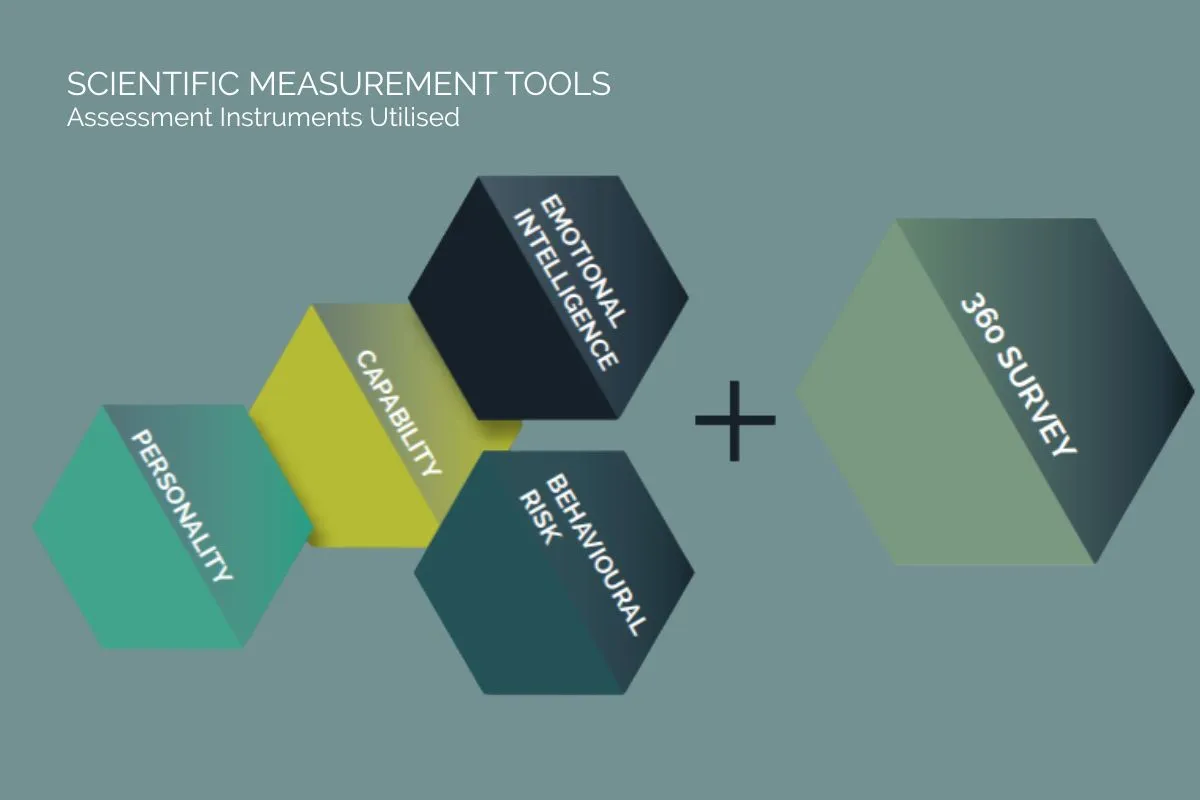

One of the core goals was to assess female candidates against key leadership competencies, offering an objective view of their strengths and development areas. Using psychometric assessments and a 360-degree survey, JVR provided a scientifically robust assessment of each participant’s leadership potential, ensuring personalised and group development plans. This approach aligns with research showing that objective assessments can reduce gender biases in leadership evaluations (Eagly & Johnson, 1990).

Why a Science-Based, Multi-Method Approach Works Best

Leadership is a complex phenomenon and a one-size-fits-all assessment approach often falls short, especially for women navigating unique challenges in the workplace. JVR’s multi-method, science-based approach combining psychometric data with 360-degree survey data, created a holistic view of each leader’s profile. In addition, our approach allowed us to assess the required leadership behaviours both from a potential and a displayed perspective, which provides powerful insights into development drivers. This method not only identified potential and displayed behaviours but also highlighted development drivers, ensuring tailored growth plans that align with organisational goals (Luthans & Peterson, 2003).

How JVR’s M³ Model Guided the Development Journey

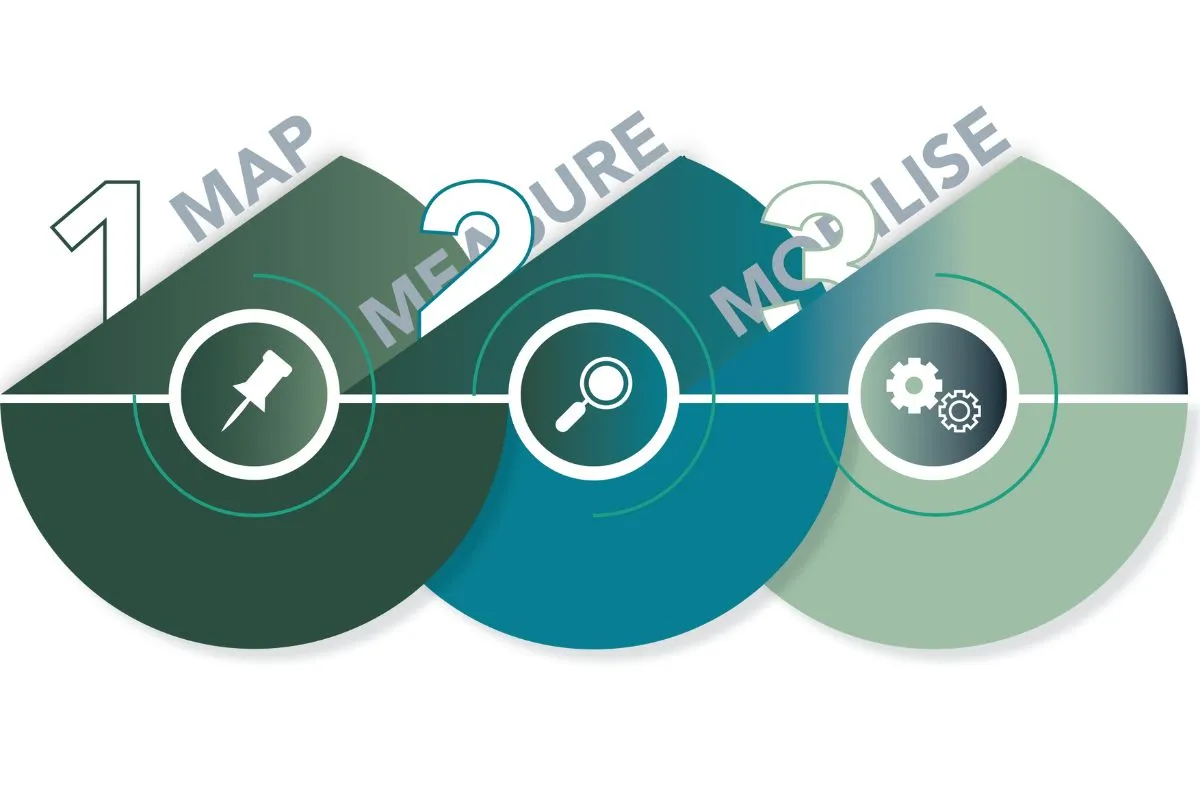

JVR’s M³ Model guided the evaluation process through three key phases, ensuring a structured and impactful approach:

Step 1 – MAP: Defining the Leadership Context

JVR considered the organisation’s goals and leadership needs within the Financial Services Industry. By identifying critical competencies, they recommended a customised solution aligned with the overall programme’s objectives.

Step 2 – MEASURE: Assessing Leadership Strengths and Gaps

Using psychometric assessments and a 360-degree survey, JVR measured leadership behaviours, uncovering strengths, blind spots, and growth areas. This multi-method approach provided objective insights as supported by research on the reliability of multisource feedback (Conway & Huffcutt, 1997).

Step 3 – MOBILISE: Turning Insights into Action

The final phase focused on translating data into actionable insights. By analysing the data of the psychometric assessments and a 360-degree survey, JVR identified specific development opportunities for each leader. These insights empowered participants to enhance their leadership competencies, fostering greater confidence and impact in their roles.

What We Learned: Key Insights from the Assessment

The assessment process delivered valuable analytical trends, including:

From a competency potential perspective, the cohort’s strength seems to be in the Enterprise Thinking competency, where the majority are likely to understand key commercial issues impacting the success of the organisation. However, from a competency displayed perspective, Enterprise Thinking is reported as an area of development. Therefore, from a group development perspective, this gives further insight that the cohort may not always be comfortable when required to display the behaviour effectively. Furthermore, it is in this area where the most individuals were rated as requiring individual development based on the 360-degree survey results.

From a competency potential and displayed competency perspective, both Channelling Innovation and Synergising were identified as development areas. This suggests that a vast majority of the group seems to need development when they are required to facilitate the creative processes of others and encourage others to explore opportunities. They may also not be comfortable when required to foster and leverage collaborative efforts within and across teams.

The data also indicated that the cohort may be performing tasks and showing behaviours that do not come naturally to them. This could be the result of learned behaviour or that their colleagues rated them in an overly positive manner as part of the 360-degree survey. A possible implication could be that, should underlying competency potential be lower than what is being displayed by the individual, these areas may not be as apparent during times of pressure and change or over longer periods.

From a Counterproductive Work Behaviour (CWB) perspective, the data suggest that, when the cohort is not managing their behaviour, almost two-thirds of them may become overly cautious and risk-averse. They may avoid making risky decisions and delay decision-making processes. The majority of the cohort, preferring to work alone, may become magnified when they are experiencing stress. As managers, they may not always be available to the team and offer them support where needed.

From a Values perspective, the data suggest that two-thirds of the cohort seem to be motivated in an environment that provides job and financial security. This is consistent with Prudence being identified as a strength in the personality results. Similarly, as one-third of the group seems to prefer a culture of tradition and upholding customs, the group may be somewhat resistant to or struggle with change. This is consistent with the lower Inquisitive score in the personality assessment. The group may have strong preferences for tried and tested methods and may not actively look for new ways of doing things.

Each participant received a 60-minute feedback session with a structured development report, followed by a 90-minute coaching session to cocreate an individual development plan. This process ensured actionable steps for growth (Barkhuizen et al., 2022).

The Impact: Advancing Inclusion Through Female Leadership

This collaboration underscores the power of a scientific approach to female leadership development. By investing in female talent, the South African Financial Services Group is building a more inclusive leadership pipeline. The programme’s success highlights the value of tailored interventions that combine rigorous assessment with personalised coaching, equipping women to thrive in a competitive industry.

What Organisations Can Learn from This Programme

Organisations can replicate this approach to foster female leadership development:

Use Multi-Method Assessments: Combine psychometric assessments and 360-degree surveys for a comprehensive view of leadership potential.

Tailor Development Plans: Create individualised plans based on assessment insights to address specific strengths and gaps.

Invest in Coaching: Provide one-on-one coaching to translate insights into actionable growth strategies.

Explore JVR’s leadership development solutions by contacting us at consulting@jvrafrica.co.za for more information.

Want to learn more about this project? Watch the webinar that the blog article is based on.

References

Barkhuizen, E. N., Masakane, G., & van der Sluis, L. (2022). In search of factors that hinder the career advancement of women to senior leadership positions. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 20, a1898.

Conway, J. M., & Huffcutt, A. I. (1997). Psychometric properties of multisource performance ratings: A meta-analysis of subordinate, supervisor, peer, and self-ratings. Human Performance, 10(4), 331–36.

Eagly, A. H., & Johnson, B. T. (1990). Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 233–256

Luthans, F., & Peterson, S. J. (2003). 360-degree feedback with systematic coaching: Empirical analysis suggests a winning combination. Human Resource Management, 42(3), 243–256.

Share this post

Newsletter

Get up-to-date industry news right in your inbox